Queer Lindy Hoppers of the Harlem Renaissance - Why we never hear about LGBTQ* dancers from history

Despite societal pressures and legal restrictions, a vibrant and visible queer world thrived in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s, significantly influencing and participating in the era’s culture.1cf Riemer&Brown, p. 56; for an accessible introductions to Queer Harlem Renaissance, check out Johnson’s Flamboyants. The Queer Harlem Renaissance I Wish I’d Known While we regularly mention icons like Frankie Manning and Norma Miller, we never highlight any LGBTQ+ dancers.2Some authors mention that dancers like Leon James and Al Minns were rumored to have been queer (Fürnkranz, p. 43); however, there does not seem to be a lot of evidence for this. Even though we may never find a famous queer Lindy Hopper from the old days, the evidence shows that queer people were actively participating in and shaping a social dance scene, especially in private and semi-public spaces.

This lack of historical visibility isn’t just a problem we encounter when it comes to the history of Lindy Hop; it’s a reflection of how we’ve often viewed pre-Stonewall queer life in general. Even though we often think of the Stonewall riots “as the beginning of the LGBT movement”, some historians nowadays argue that they should rather be seen as “the catalyst for a new wave of radical militancy in [queer]3As Riemer and Brown point out in their book We are Everywhere: “Professor Chauncey’s essential work, Gay New York, focuses almost entirely on what he referred to as the ‘gay male world’; readers may take issue with our reformulation of Chauncey’s work to include queer people as opposed to just gay men. Please note that we do not universally apply Chaucney’s analysis to other communities, though we do so in some circumstances. Most important, we identify transgender lives when warranted by the evidence, whereas historians of earlier generations – or even of just a few years ago – may have been less inclined to identify transgender idnividuals or communities. There is, in our minds, no question that some, if not many, of the fairies exhaustively researched by Professor Chauncey for Gay New York were not men ‘adopting the female role’; they were, instead, women, born before the language, cultural environment, and/or medical possibility to align their sex and gender.” (p. 331) politics”4Chauncey, p. xvi. But there was queer organising before as well:

Queer Life during the Harlem Renaissance

The language used to discuss queer life during the Harlem Renaissance was different from our own. The understanding of sexuality was profoundly different in the 1920s and 1930s: while we now categorize sexuality into distinct identities like homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual, people in the 1920s and 1930s were more often labeled ‘queer’ based on gender nonconformity rather than solely on their sexual behavior.6Chauncey, p. 13 This is reflected in the words used to talk about queer people: some lesbians who appeared more masculine were referred to as “bulldykes” and “bulldaggers”7The term “bulldagger” in particular almost always refers to African Americans. While it has been used as a derogatory term, it has also been “reclaimed as an honorific term through the

twentieth century, by blues singer Bessie Jackson (1897-1948) in her 1935 song, ‘B-D Woman’ and by SDiane A. Bogus and Judy Grahn, who celebrate her as a courageous and proud resister of oppression

and an essential connection, as Bogus (1994) avers, to the ‘ancient and recent black woman-loving past.’ She is an avatar of black female sovereignty, linked mythically to Dahomean Amazons and Queen Califia, namesake of California.” (Caputi, p. 136), whereas gay men who appeared more feminine were called “pansies”, “fairies” and “fags”.8Wilson, p. 21.

The terms “bulldagger,” “pansy,” and “fairy,” among others, were often used by the dominant society as slurs to demean individuals who transgressed gender norms. However, within the queer communities of the Harlem Renaissance, some of these terms were reclaimed and used as a form of self-identification and solidarity. (see e.g. Caputi, p. 136; Madden, p. 515).This dual usage reflects a common historical pattern where marginalized groups adapt and repurpose language used against them. The word “queer” itself has undergone a similar transformation, shifting from a historical slur to a widely-used and reclaimed term within contemporary LGBTQ+ communities.

Queer people who did not fit the gender-bending stereotypes were often protected from discrimination by “the straight world’s ignorance”9Chauncey, p. 103: “[m]en and women who did not fall into these categories were much more able to experiment with same-sex trysts or establish lasting relationships and avoid being found out”10Wilson, p. 21.

Next to Greenwich Village, Harlem was considered to be “the most exciting center of gay life” by many11Chauncey, p. 227; This does not mean that Harlem could be said to have been a gay neighborhood in the 1920s, but it allowed a queer enclave to take shape (cf. Chauncey, p. 228.. It was the “only place where [B]lack gay men could congregate in commercial establishments, and they were centrally involved in many of the currents of Harlem culture”12Chauncey, p. 227.

This queer presence in Harlem must be understood in an intersectional context.13Intersectionality is a framework for understanding how different social and political identities—such as race, gender, class, and sexual orientation—combine to create unique experiences of discrimination and privilege. It recognizes that these identities don’t exist independently; they overlap and influence one another, shaping a person’s lived reality in ways that can’t be explained by looking at any single identity alone./13: for Black queer individuals the Harlem Renaissance was both a cultural explosion and a daily negotiation of racism, sexism, and homophobia. Living in a multiply marginalized body meant navigating a world shaped by both racial segregation and homophobia. Racist policing, segregation laws, and economic exploitation intersected with societal hostility toward gender and sexual nonconformity14Consider, for example, Langston Hughes, a gay writer: he had to leave Columbia University “due to the immense racism he received from classmates”. Bessie Smith, a queer jazz singer, died in a car accident; it was long rumored that she died because she was not admitted to a white-only hospital. While this rumor has since been debunked, this example still helps to illuminate the context of the 1920s and 1930s. (Johnson) In this context, finding protected spaces was not only an act of sexual self-determination but also one of racial self-assertion. The safe spaces carved out by the community were not just for dancing or dating; they were acts of resistance against multiple layers of oppression. Many of these spaces were nurtured by musicians, club owners, and performers who were themselves queer, creating environments where both music and dance thrived in ways that were inseparable from queer Black life.

Private and semi-private gatherings became vital sanctuaries where Black queer individuals could express themselves without the gaze or control of white society.

Dancing in the Shadows: Private Parties and Rent Parties

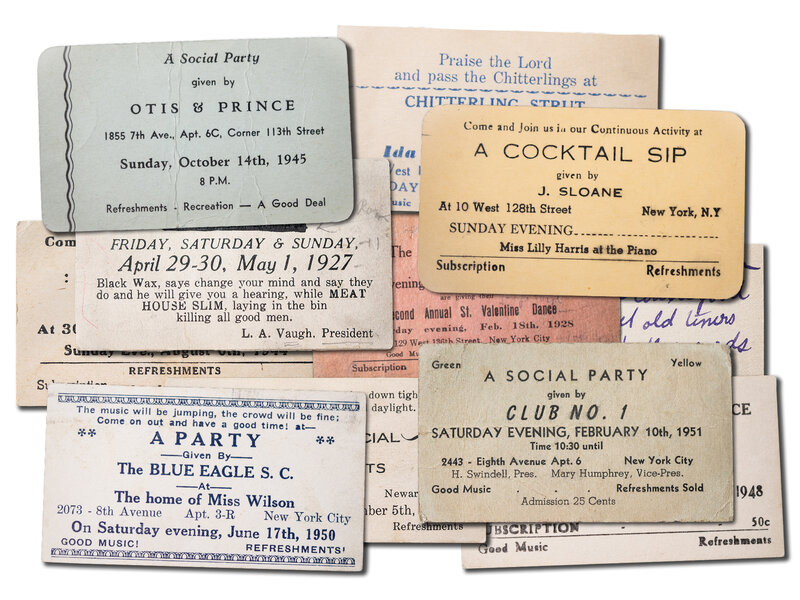

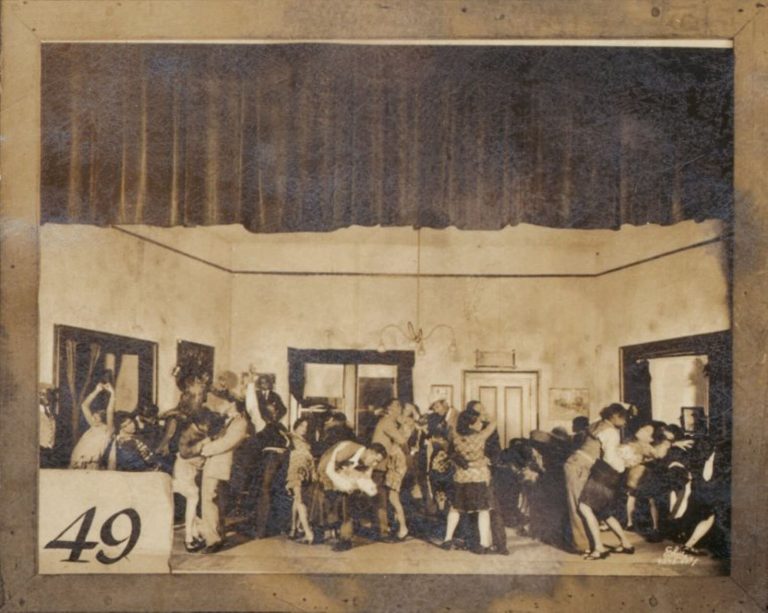

During the 1920s and 30s, private parties in particular seemed to be a main cornerstone of queer social life15Chauncey, p. 278 and were “the safest way for lesbians and gay men to meet, sing, dance, and drink plenty of bootlegged alcohol”16Wilson, p. 64. While some of these were events put on for friends, others had a much different goal: so-called rent parties became a vibrant part of Harlem culture. These parties were held to help residents make rent after white landlords raised prices to exorbitant levels. Guests were charged a small admission fee, and food and bootlegged alcohol were sold at an additional cost. Woolner mentions that rent parties “were at first usually managed by women, some of whom were former (or current) madams or entertainers”17Woolner, p. 166.

The parties quickly became “one of the most colorful of Harlem institutions”18Thurman, p. 287, according to one account from the period. These events ranged from small, invitation-only gatherings to immense, regularly scheduled events that were fixtures on the gay social calendar.19Chauncey, p. 279 A newspaper article from 1926 described the lively atmosphere: “Booze of dubious origin can be secured from the nearest delicatessen, and under its enlivening influence the guests can indulge in the energetic dance movements of the day, until the floor threatens to give way or the neighbors summon the police.”20A Rent Party Tragedy,” New York Age, December 11, 1926, as quoted in Woolner

It seems that, for a lot of queer people, dancing was mostly possible at private events, such as rent parties – these were understandably a lot less regulated than commercial institutions that were “concerned about police surveillance”21Chauncey, p. 278 and therefore “provided protected spaces for lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men to meet and mingle”22Wilson, p. 31. For Black women—particularly lesbian and bisexual artists—these spaces offered a way to subvert both patriarchal and racist constraints, allowing freedom in dress, movement, language, and intimacy23cf. Woolner, p. 153, 155, 177.

There are only a few direct reports available, partly because of the intended secretiveness of some of the more private parties25Wilson, p. 65. Chauncey quotes gay men talking about a rent party followed by a “second, more intimate party […] where men could kiss as well as dance to slow music“26Chauncey, p. 279.

Wilson quotes Mabel Hampton talking about another private party:

Creating Public Spaces: Performers, Speakeasies, and Drag Balls

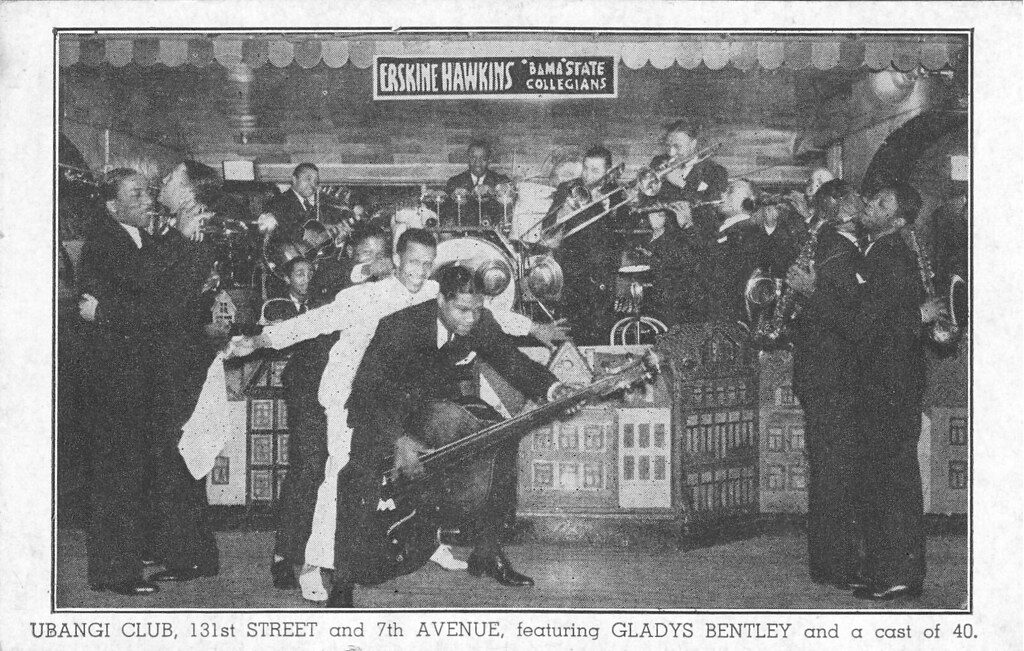

Alongside male stars such as Duke Ellington, queer Black women also shaped the Swing and Jazz scene of the era. Ma Rainey, often called the “Mother of the Blues,” sang openly about relationships with women in her lyrics30Carby, p. 475 & 479, embedding lesbian and bisexual desire into popular music decades before public acceptance. Tiny Davis, a trumpeter and bandleader, was a standout figure in Swing who later in the 1950s lived openly with her partner Ruby Lucas31Gould. Her group, the “International Sweethearts of Rhythm,” became a powerful symbol of queer presence in a male-dominated jazz world. After leaving the US, Ada “Bricktop” Smith, a singer, dancer, and legendary club owner, created venues where Black and queer people were welcome, e.g. in Paris and in Mexico City. Through her stage charisma and business sense, she crafted spaces where Black queer culture could be visible, celebrated, and economically sustainable.32Bendix The existence of places such as Bricktop’s club was not accidental but the result of intentional community-building by Black queer women who understood the necessity of safe, self-determined spaces for both artistic expression and queer life.33Bricktop, for example, was a supporter (and, in case of the former, lover) of both Josephine Baker (Niven) and Mabel Mercer (Smith).

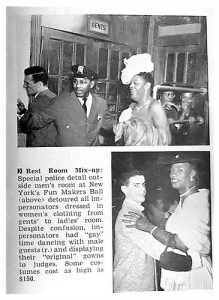

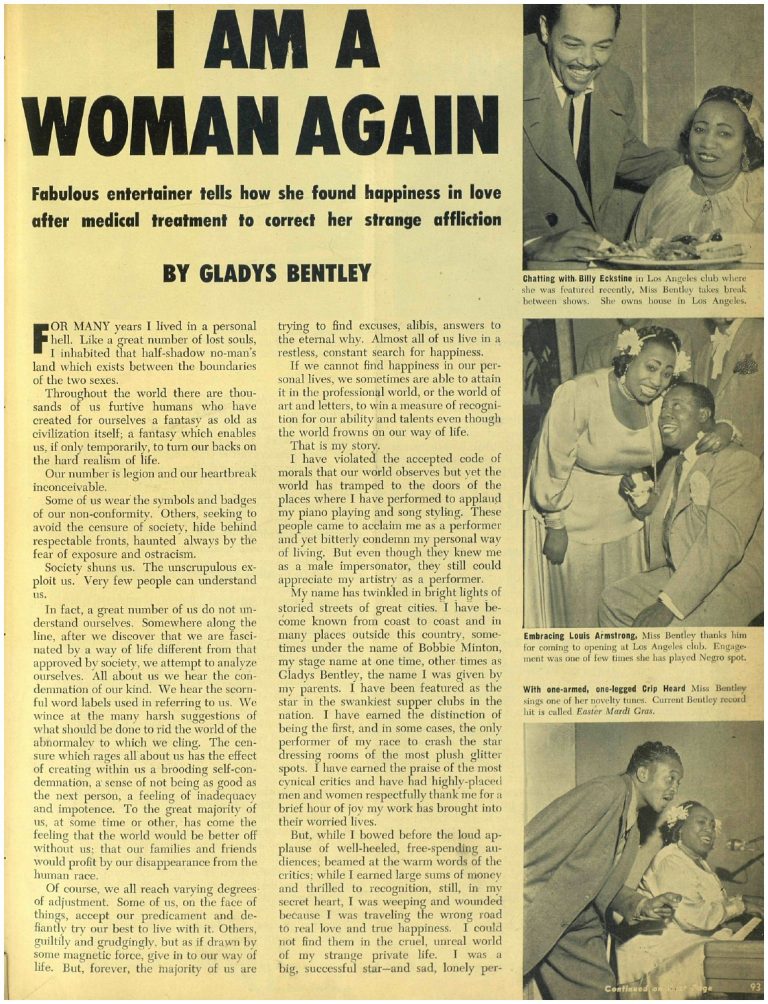

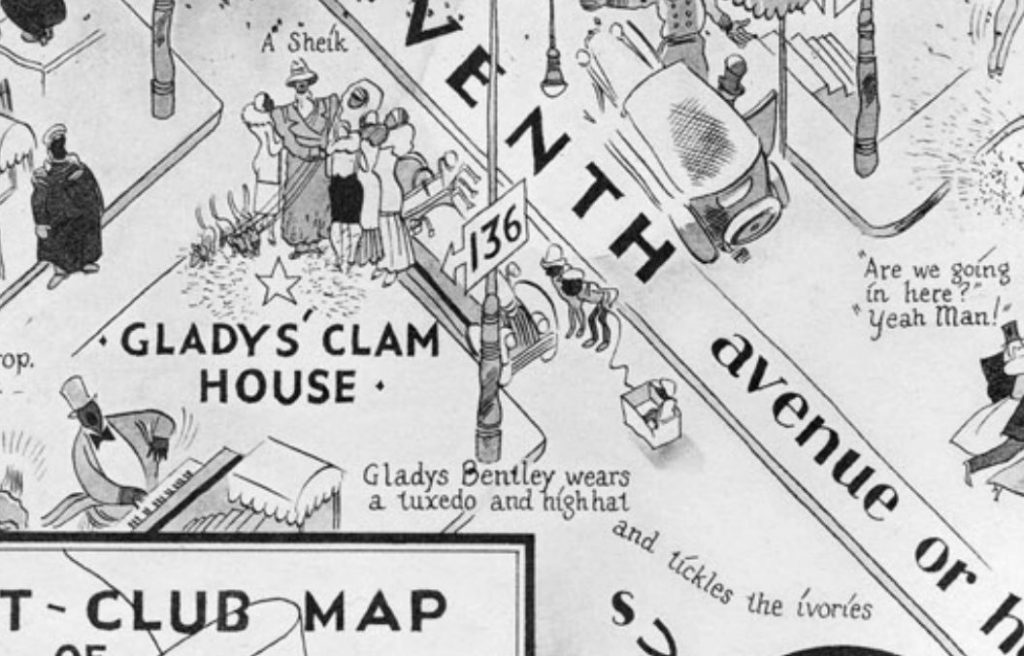

Some performers deliberatley broke with traditional gender norms. There were so-called ‘female impersonators’34Garber, p. 324, i.e. what we would understood nowadays as drag queens. Gladys Bentley, “an avowed ‘bulldagger'”35Wilson, p. 210, was not only known for her risqué songs and musical prowess, but also for her male attire. She even married a white woman “in a very publicized New Jersey civil ceremony”36Wilson, p. 210.

While performers like Bentley could find success, the experience for regular patrons in public venues was often more complex: queer patrons couldn’t always be themselves37Woolner, p. 173, and these spaces were also sometimes inaccessible to the Black working class38Wilson, p. 37.

Despite queer social life often separating gay men and lesbians into different circles, certain semi-public spaces like speakeasies and drag balls served as crucial points of convergence.39Chauncey, p. 228 The extent to which patrons could be visibly queer in Harlem speakeasies is a subject of historical debate; however, Woolner references an investigator’s report on a speakeasy in which “eight colored women […], all intoxicated, […] danced among themselves, doing eccentric dancing, and ballroom dancing”40Woolner, 175.

Another report about a speakeasy mentions a similar scene:

One of the most visible beacons of queer life were the Harlem drag balls (see pictures below) that “attracted people from across the region, were known in Europe, and understood themselves to be part of a tradition of such balls beginning in the late nineteenth century and reaching into the 1930s”42Chauncey, xvii. The biggest such event was the Hamilton Lodge Ball, “the largest annual gathering of lesbians and gay men in Harlem”43Chauncey, p. 257 and all of New York City. Drag balls were events “at which gay men dressed in women’s clothes and danced together”44Chauncey, p. 291. Even the Savoy Ballroom hosted drag balls45Chauncey, p. 294.

Challenges and Shifting Tides: The 1930s Backlash

Still, a higher queer visibility should not be taken as acceptance or safety49Riemer&Brown, p. 58; Chauncey, p. 253; Johnson (“I think grudging tolerance better describes what

queer people experienced during that time.”): one of the most famous African-American clergyman, Adam Clayton Powell, launched multiple attacks on homosexuality in 1929, decrying it as something ‘immoral’50Chauncey, p. 254f. Wilson writes that “lesbians and gay men relied on private parties as spaces safe from potential personal and professional scandal and from prosecution”51Wilson, p. 24, which fits with how a lot of the queer Black male leaders of the Harlem Renaissance in literature and philosophy never came out publicly52See e.g. Johnson on Langston Hughes (“I can only imagine that Langston, who became a leader in the Harlem Renaissance, never felt the space or security to be publicly queer. There were reasons—both internal and external—informing his decision to obscure his sexuality.”). Moreover, there were laws “criminaliz[ing] not only gay men’s narrowly ‘sexual’ behavior, but also their association with one another, their cultural styles, and their efforts to organize and speak on their own behalf”53Chauncey, 2. However, “the laws were enforced only irregularly, and indifference or curiosity – rather than hostility or fear – characterized many New Yorkers’ response to the gay world for much of the half-century before the war”54Chauncey, p. 2. This curiosity can be seen by the amount of press articles published at the time on the drag balls and queer parties55Wilson, p. 24, but also by the amount of white people going up to Harlem to experience the nightlife they had read about in books56Hughes, p. 176; Garber, p. 328. This relative indifference, however, would not last. The cultural climate began to shift drastically just a few years later.

Just as Lindy Hop managed to attract more attention in the US, queer culture was forced into hiding in the mid-1930s to the 1950s57Chauncey, p. 8. It didn’t stop queer life58Garber, p. 331 but it “did become less visible in the streets and newspapers of New York”59Chauncey, p. 9:

Once a beacon of queer social life, drag balls stopped happening: “The Hamilton Lodge drag balls, a Harlem tradition since the 1870s, ended abruptly in 1939 after a wave of panic over sex crimes seized the nation, and changed the perception of homosexuals from silly oddities and sexual degenerates to dangerous psychopaths”61Wilson, p. 256.

“What was once considered progressive, shocking, or taboo became associated with the destruction of American society and regarded as an issue of national security. Lesbians and gay men, who had been fairly visible in the early decades of the century, slunk back into the closet or declared their change in sexual orientation”62Wilson, p. 257. Gladys Bentley is a perfect example of this: “In her later years she cast off her characteristic tuxedo, claimed to be from Port-of-Spain, Trinidad—although she was born and raised in Philadelphia—and wore flowers in her hair, dresses, and pearls while performing jazz and blues standards”63Wilson, p. 211.

This backlash, in addition to all of the challenges already apparent in 1920s/early 1930s Harlem, is likely why we never hear about queer Lindy Hoppers.64As was stated above, this does not mean that queer life, and more specifically dancing, just stopped, as this quote about a gay bar in Buffalo, NY shows:

“They did so many different [dances] that I can’t really remember all the names. However, I’ll try. They did a double-time step which is similar to the lindy… [What] the heck are the other things? I guess they called them the Big Apple or crazy names… and the Shag… That’s what I think really got to me was watching the dances. . . [A] lot of different little steps that [they’d] improvise, variations of the boogie type things.” (Kennedy & Davis, p. 48)

Conclusion: Legacy and Continued Relevance for Queer Lindy Hoppers Today

When talking about queer aspects of the Harlem Renaissance, people often focus on literature (for example Langston Hughes or Richard Bruce Nugent), performers (such as Ma Rainey or Bessey Smith) and sometimes on composers (Billy Strayhorn) or philosophers (Alain Locke)65Again, Johnson’s book Flamboyants is highly recommended to everyone interested in queer icons from the Harlem Renaissance. While we lack singular queer Lindy Hop icons, the historical record reveals that queer people were a part of the social dance scene, if often insivible. Queerness was a present and visible part of the birthplace and cultural context of Lindy Hop, and thus can be seen as inherently connected to the dance’s legacy.

Instead of looking to heroify singular (queer) dancers, I suggest we take a more comprehensive perspective. Lindy Hop was not shaped by only one or two dancers; the root of the dance were communal and diverse. It was made by people, not just famous couples on a stage; in private homes, not just in dance halls. The spirit of those early queer dancers, carving out space to dance freely, is a powerful legacy. It’s a reminder that building a truly inclusive scene today means more than just being a litle ‘accepting’; it means actively creating spaces where people can be their whole selves.

- Bendix, Trish: "Queer Women History Forgot: Ada 'Bricktop' Smith."

- Caputi, Jane: "Bulldagger." In: Zimmermann, Bonnie (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures. Volume 1. Lesbian Histories and Cultures. An Encyclopedia. Routledge: New York, 2012. pp. 136-137.

- Carby, Hazel V.: "It Jus Be’s Dat Way Sometime: The Sexual Politics of Women’s Blues". In: O'Meally, Robert G. (Ed.): The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. Columbia University Press: New York, 1998. pp. 470-483.

- Chauncey, George: Gay New York. Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. Basic Books: New York, 2019.

- Fürnkranz, Magdalena: "Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject in Jazz in the 1920s." In: Reddan, James, Herzig, Monika & Kahr, Michael (Ed): The Routledge Companion to Jazz and Gender. Routledge: New York, 2022.

- Garber, Eric: "A Spectacle in Color: The Lesbian and Gay Subculture of Jazz Age Harlem." In: Duberman, Martin B., Vicinus, Martha & Chauncey, George (Ed.): Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. Penguin: New York, 1990.

- Gould, Lauryn: "Tiny Davis".

- Johnson, George M.: Flamboyants. The Queer Harlem Renaissance I Wish I'd Known. Farrar Straus Giroux Books for Young Readers: New York, 2024.

- Hughes, Langston et al: The Collected Works of Langston Hughes. University of Missouri Press: 2001.

- Kamin, Debra: "The Rent Was Too High So They Threw A Party." New York Times, 28th March 2024.

- Kelly, Trent: "Ubangi Club". Flickr.

- Kennedy, Elizabeth Lapovksy & Davis, Madeline D: Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold. The History of a Lesbian Community. Routledge: New York/London, 1993.

- Madden, Ed: "Flowers and Birds." In: Haggerty, George E. (Ed): Gay Histories and Cultures. Garland: New York/London, 2000. pp. 513-516.

- Manning, Frankie & Millman, Cynthia R.: Frankie Manning. Ambassador of Lindy Hop. Temple University Press: 2009.

- Miller, Norma & Jensen, Evette: Swingin' at the Savoy. The Memoir of a Jazz Dancer. Temple University Press: 1996.

- Riemer, Matthew & Brown, Leighton: We are Everywhere. Protest, Power, and Pride in the History of Queer Liberation. Ten Speed Spress: California/New York, 2019.

- Smith, Patricia Juliana: "Mercer, Mabel." glbtqarchive.com.

- Thurman, Wallace: "Aunt Hagar's Children". In: Singh, Amritjit & Scott III., Daniel M. (Ed.): The Collected Writing of Wallace Thurman. A Harlem Renaissance Reader. Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick/London, 2003.

- Wilson, James F: Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance. University of Michigan Press: 2010.

- Woolner, Cookie: The Famous Lady Lovers. Black Women & Queer Desire before Stonewall. The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2023.